Blog

The first draft of the 2024 IECC is available for review. In this blog post, get an overview of the residential code requirements in the current draft.

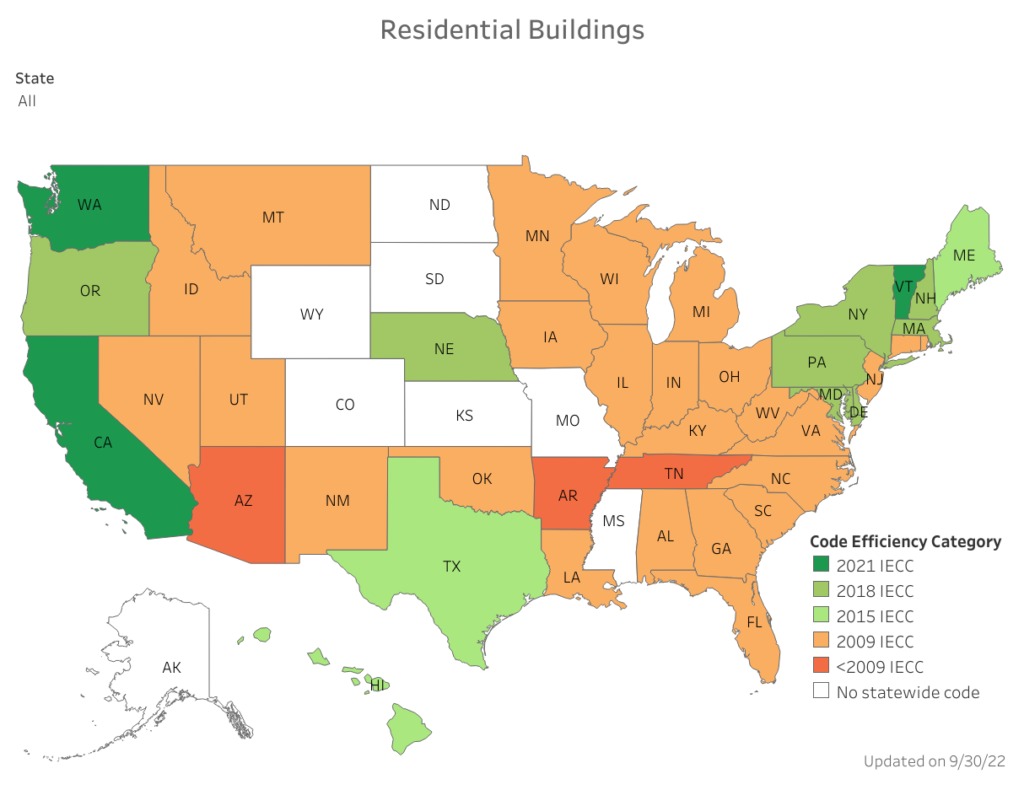

Each state in the U.S. can adopt its own residential building code. States tend to use a specific edition of the IECC as their residential code (with the exception of California). And while 2022 is nearly over, only a few states have adopted the 2021 IECC.

However, several more states are likely to use the 2021 IECC given that under the Inflation Reduction Act, an additional $1 billion has been allocated to support jurisdictions in adopting the 2021 IECC or its zero-energy appendices.

Due to its lack of country-wide adoption, most building professionals might not be familiar with the 2021 IECC as it compares to the current codes in the states where they work. For example, there are significant increases in the minimum insulation requirements, changes to the air leakage test thresholds, and a new section, R408, with requirements to achieve “additional efficiency” through the selection of “packages.”

While most haven’t had a chance to become familiar with the 2021 IECC, the next iteration, the 2024 IECC, has been under development for over a year. The first draft is already available for review and open to public comment through mid-December 2022.

Keep reading to learn about the process and deliberations that led to this draft and get an overview of the first draft of the 2024 IECC-R.

Compared to previous code cycles, this time, the IECC is being developed following a process typically used for “Standards.” This just means that the proposals move through the evaluation process a bit differently than in years past.

A diverse and balanced voting body of 48 members hears each proposal and votes, often (but not always) following the recommendation of a Sub-Committee that first heard and debated it.

In October 2021, about 200 code-change proposals were submitted for consideration and assigned to one of five Residential Sub-Committees (Envelope, HVAC, Existing Buildings, Modeling, and Electrical & Renewables). The Sub-Committees are diverse and composed of both IECC Residential Consensus Committee members as well as other individuals.

By late September 2022, the Residential Consensus Committee had heard and voted on all 200+ proposals. About half failed to earn approval of two-thirds of the voting members and therefore do not appear in the first draft of the 2024 IECC-R.

The others achieved the support of two-thirds of the voting members—in some cases, after lengthy debate. While some proposals were approved “as submitted,” many were modified by the Committee in order to reach consensus.

Ultimately, a proposal emerged to combine 12 of these proposals into one ‘omnibus’ proposal. Members then worked to identify specific edits to each of the 12 proposals that, when combined, could earn support of the two-thirds majority.

The Omnibus achieved a better balance of requirements and became more palatable when presented as a package solution with consideration of combined costs and benefits.

For example, in the consensus-building process, rather than requiring 100% of parking spaces in low-rise multifamily to be EV-ready or EV-capable, the percentage was reduced to 40% after considering cost estimations. And, so as to not lose this important measure in single-family homes, it was kept in the main body of the code by adding some “exceptions.”

Other modifications included:

At the end of the negotiations, a diverse group of 15 of the 48 voting members agreed to sign on as unofficial co-proponents of the Omnibus, and the proposal surpassed the two-thirds majority needed for approval.

While the proposal contained requirements or language that some members may not have supported as an individual code change, they were willing to support the Omnibus because it also contained other code changes that they did support, offering a more balanced path forward.

We’ll start with what you won’t see in the first draft: A ban on the use of fossil fuels, embodied carbon accounting, and a mandate for solar PV or electric vehicle chargers in residential new construction projects.

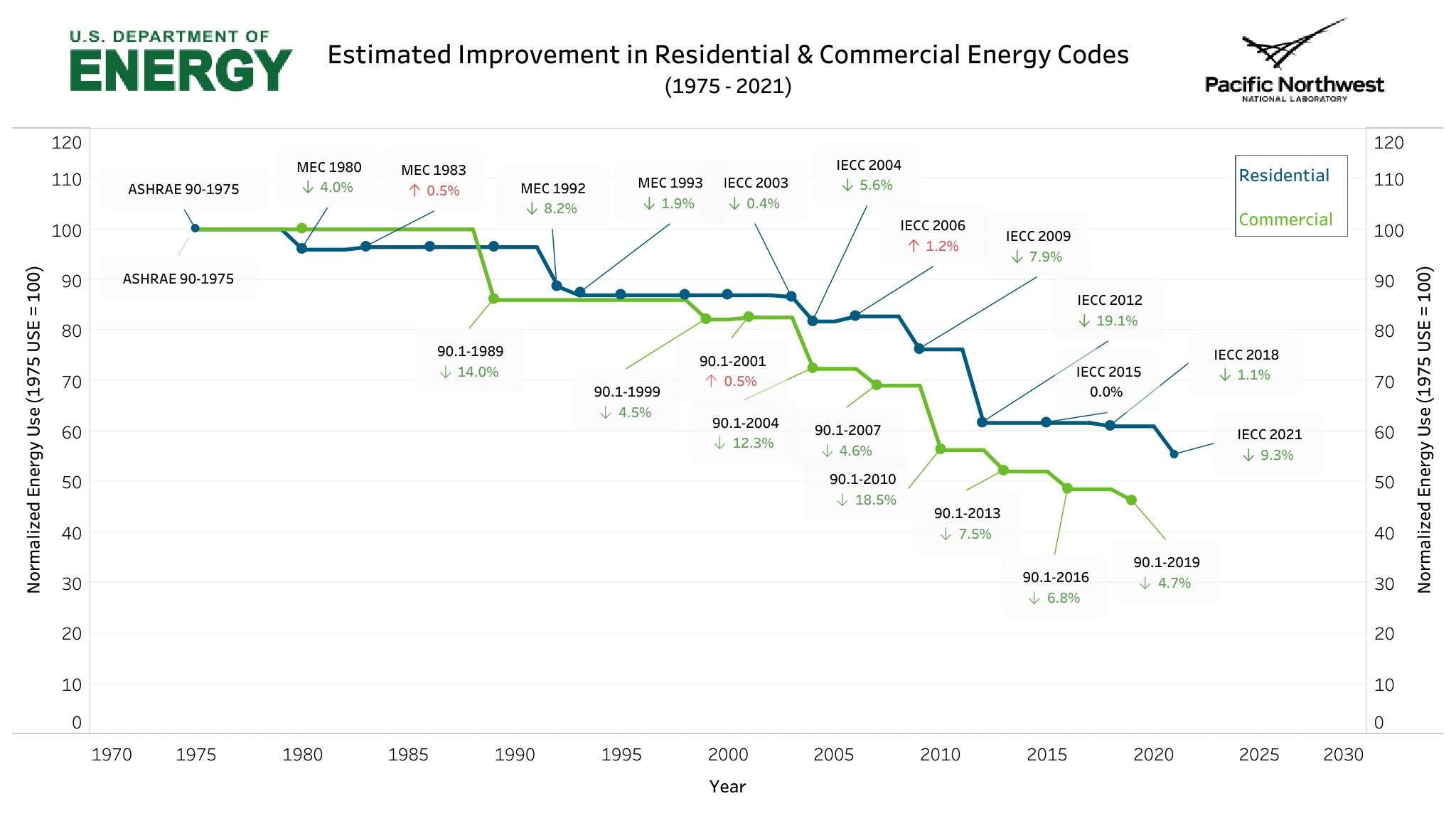

However, the IECC Residential Consensus Committee, which evaluates residential code change proposals, was charged with “developing a glide path to zero energy by the 2030 IECC.”

The 2024 IECC draft makes some initial progress in that direction by adding new requirements, increasing stringency in current requirements, and also taking a comprehensive look at the three compliance pathways to ensure each path achieves similar performance.

One proposal that had broad support of voting members was to expand, rename, and restructure the 2021 IECC Section R408 (“Additional Efficiency Package Options”) to a points-based system that provides more opportunities to achieve “additional efficiency” when using the Prescriptive compliance path.

Structured to provide points that reflect the energy savings of specific measures in their respective climate zones, the point system allows more flexibility to achieve the 10 points (roughly 10% energy savings). The new R408 also allows onsite renewable energy systems on equal footing with other measurers for meeting the 10-point target.

While it was always intended for the Energy Rating Index path to provide similar flexibility, the max ERI values in the 2021 IECC include stringent values, ranging from 48-52. This ultimately made the ERI a less popular path given the level of rigor in energy efficiency measures it takes to meet those values.

The first draft of the 2024 IECC significantly updates this section to ensure more parity with the other compliance paths. Rather than lowering the max ERI further, changes were approved that make it more aligned with a HERS Index in the low 50s and allows on-site renewables to be used, if a lower ERI (40) is met.

The other modeling path, R405, was also substantially revised to increase the required cost and energy savings over the reference design, allowing credit for HVAC and DHW system efficiency and duct location and establishing a more rigorous envelope backstop.

In terms of getting us on that “glide path” to zero energy, there are four areas of “readiness” that are in the first draft and are required regardless of which compliance path is followed:

Other incremental changes include:

If you have opinions about what made it in or what was left out of the first draft, please participate in the public comment period. Consider joining a Sub-Committee or attending meetings (starting back up in January 2023).

The IECC Residential Consensus Committee’s next task will be to review public comments received and determine what changes, if any, should be made before the second public comment draft—while keeping in mind that the final draft of the 2024 IECC must be ready by the end of 2023!

Still have questions? Leave a comment below or contact us to reach an expert from our residential building services team.

Contributor: Gayathri Vijayakumar, Principal Mechanical Engineer at SWA and voting member of the IECC Residential Consensus Committee

Steven Winter Associates