Blog

Modern air-source heat pumps (ASHPs) can provide reliable, efficient, clean, affordable, and sustainable heating and cooling.

As I’ve written in several posts [1], electrification is all the rage. Modern air-source heat pumps (ASHPs) are fantastic technologies, and they can provide reliable, efficient, clean, affordable, and sustainable heating and cooling when done well and in the right application. I worry that these caveats are too often glossed over. I’ve also seen really bad heat pump installations, and I think it’s easier to screw up a heat pump than a boiler or furnace.

This post is an overview of the process I suggest for good ASHP installations. I’ll be doing a post for each of the steps here, but this first post is an outline of the whole process because I believe the whole process is really important. The focus here is on homes, mainly in colder climates, and I’m not talking about VRF systems. I use the generic second person, so “you” can refer to different people in different steps.

1. Be clear about your goals. Why are you considering a heat pump? For cooling? To save money (now or later)? To get rid of on-site fuels? For health and safety? Practicality? Comfort? To reduce CO2 emissions? Do you want to heat and cool the whole house or just one space? Any or all of these can be viable. How you approach a project, design systems, and select equipment really depends on goals. For example, if you’re primarily interested in cooling, that may change how you consider heat pump performance in cold weather. What follows generally focuses on systems that provide most (or all) heating and cooling to most (or all) of a home.

2. Consider the envelope. For many reasons, ASHPs are more effective in homes with lower loads. Really think about practical envelope improvements before you install a heat pump.

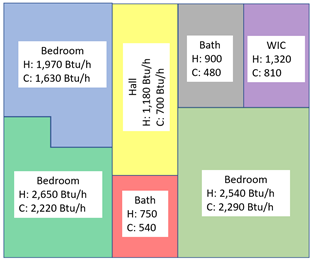

3. Calculate design heating and cooling loads accurately. Let me emphasize accurately. ACCA Manual J is the industry standard, but in my experience, Manual J design loads are quite a bit higher than reality. I have my own spreadsheet based on ASHRAE Fundamentals, but very few folks are going to do that. Regardless of the tool you use:

4a. Determine configuration and distribution strategy. Use 1:1 ASHPs when possible; avoid multi-zone heat pumps. Are you looking for a ductless solution for one or two spaces? Does a ducted system make sense for an entire floor? Or one central heat pump? Multiple heat pumps? Consider how you might use existing ducts or add new ducts when necessary.

4b. Select right-sized, climate-appropriate equipment. ACCA Manual S focuses on this step, but it’s for all types of heating/cooling equipment. Observant readers may see there are two #4 steps. That’s because you may have to go back and forth between steps a and b. My simplified take on this:

There’s kind of an art to selecting the best systems. It’s an art based on hard numbers, but outside-the-box thinking can be very helpful.

5. Proper ducts and distribution. Proper use of ACCA Manual D results in great duct design and distribution. ASHRAE duct sizing methods are also very good. Pay attention to details and big pressure drops (e.g., high MERV filters, which I often recommend). Also pay attention to available static from air handlers (you might have to go back to the steps #4a and b). Make ducts air-tight, use smooth fittings and transitions, and don’t run ducts in unconditioned spaces.

6. Select proper controls. Wall mounted thermostats are recommended over hand-held remote controls. If other/backup heating is used aside from the ASHP, consider automatic controls that will prioritize the ASHP and switch to backup heat only when necessary. This is not always straightforward, and you may need to do some research into specific products or control systems.

7. Good installation. This is a big, important category – too big to summarize now. Good installation is critical for efficient, reliable, and comfortable ASHP operation. I covered this in some previous posts, but I’ll revisit soon. Also see some of Jon Harrod’s excellent posts on GBA.

8. Proper operation and maintenance. People using the heat pump need to know how to operate it, how to use controls, how to operate other heating systems (if present), when and how to change or clean filters, when professional service is needed, etc.

Basically, I think heat pumps need to be designed thoughtfully and installed conscientiously to perform well. I’ve seen way too much oversizing, one-size-fits all “designs,” slap-dash installations, and very disappointed homeowners. I’ve also seen very accurate load calcs, great equipment selection, and meticulous installation lead to results that exceed everyone’s expectations. I recommend the latter.

Next up: Step 1 – Be clear about goals

[1] https://www.swinter.com/party-walls/heat-pumps-are-taking-over/

https://www.swinter.com/party-walls/air-source-heat-pumps-cold-climates-part-ii

https://www.swinter.com/party-walls/air-source-heat-pumps-cold-climates-part-iii-outdoor-units

https://www.swinter.com/party-walls/electrify-everything-part-1

https://www.swinter.com/party-walls/electrify-everything-part-2

Robb Aldrich