Blog

The buildings we live, work and play in impact our health. With certain building and design considerations, we can make these impacts beneficial.

As humans, we spend a lot of time indoors. Studies by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency indicate that under normal circumstances the average American spends over 90% of their life indoors. With the spread of COVID-19 and widespread voluntary and involuntary quarantine, the rise of work from home policies and new direction to social distance has resulted in a further increase to the amount of time we spend indoors. Now more than ever, people are cognizant of the air they’re breathing and the surfaces they’re touching. The buildings that we live, work and play in impact our physical and mental health. With certain building and design considerations, we can make these impacts beneficial.

We recruited some experts at SWA to fill us in on the various considerations when it comes to the health and comfort of a building, as well as some certifications that assure these considerations are met.

Additional time spent at home is a good time to consider if our living environment is optimized to support our long-term health. One of the keys to a healthy living environment is high quality indoor air and the means by which we maintain the quality of our breathing air is ventilation.

Why do we ventilate buildings? Simply put, ventilation removes contaminants that accumulate in the indoor air and replaces it with outdoor air that is not contaminated. There are several ways to ventilate, but not all techniques are created equal. Most buildings have exhaust-only ventilation systems. This type of system is characterized by local mechanical exhaust fans, operated intermittently, which typically remove air from the kitchen or bathroom. But where does the fresh air that replaces this exhausted air come from? If you have no idea, you’re not entirely alone. In an exhaust-only ventilation system the living environment is likely assumed to operate under some gradient of negative pressure. So, the air that is replacing the exhausted air will be pulled into the living environment from an adjacent corridor, an open window, or your neighbor’s apartment. It might be pulled through the wall assembly, the crawl space, a crack in the foundation, or some combination of the above. I think we can agree that it would be in our best interest to control the quality of the air we breathe, therefore, shouldn’t we know its point of origin? And, if you don’t know where your breathing air is sourced from, how do you filter it?

There is a better way. Continuous balanced ventilation systems, combined with air sealing and compartmentalization, provide more control over the air we breathe. In a continuous balanced ventilation system, air is constantly exhausted from the kitchen and bathroom at low volumes and is replaced with an equal amount of continuously supplied air from a known origin via a dedicated outdoor air duct. The living environment is pressure balanced with an equal volume of supply air and exhaust air. As a result, the air in our breathing zone is no longer being pulled from parts unknown. Balanced ventilation systems operate best with the installation of a continuous air barrier system in exterior wall assemblies, and compartmentalization measures between apartments, decreasing the amount of air that is pulled from adjacent apartments and through wall assemblies. There are additional benefits, such as decreasing transmission of odor, smoke, sound, and pests. With a continuous balanced ventilation system, and the appropriate compartmentalization and air sealing measures, we now own the breathing zone. We know the origin of our breathing air, and the inclusion of dedicated ducted supply air offers the opportunity for further quality control through filtration of supply air and the potential for heat and moisture recovery from exhaust air for optimized comfort.

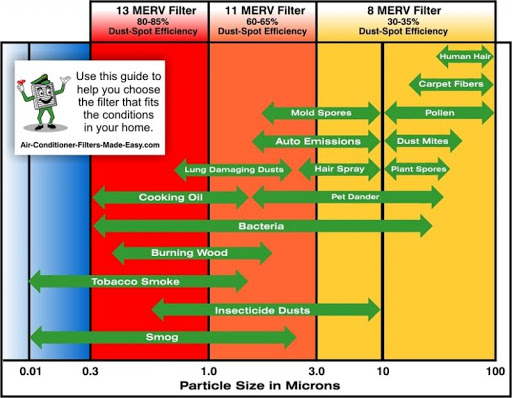

Something else that you should consider, or rather do, is replace your air-handler filter and determine if you can install a minimum MERV13 to filter particulate matter (PM) 2.5 and less.

Contributor: Thomas Moore, Building Systems Analyst

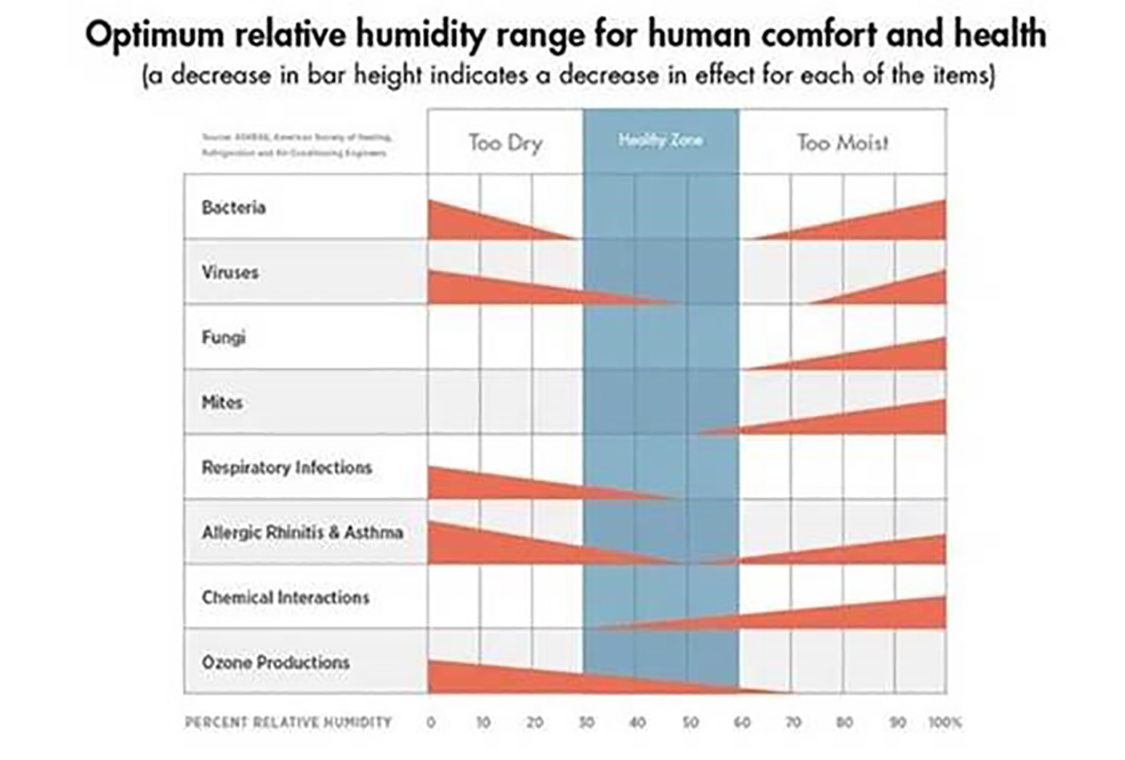

Thermal comfort – favorable temperature and humidity conditions – is fundamental to wellness and the proper functioning of any occupied space. When indoor environments are too warm, there is evidence of increased sick building syndrome symptoms resulting in occupants’ negative moods, increased heart rate, respiratory symptoms, and overall feelings of fatigue. Relative humidity (RH) that is below 20% can cause dry eyes, skin, and mucous membranes. On the other hand, high relative humidity (above 70%) may lead to stuffiness and/or mold and fungus growth. Mold and fungi produce allergens (causing allergic reactions), irritants, and in some cases, potentially toxic substances (mycotoxins). In general, I recommend conducting regular inspections of roofing, plumbing, ceilings and HVAC equipment to identify sources of moisture and potential condensation. When moisture or mildew is present, immediately address the source and replace contaminated materials. Limit areas of the building that are routinely wet because of their use (think bathrooms and kitchens) and provide a means for drying them out when they do get wet.

This CDC study details the clear link between damp environments and respiratory illness.

Of particular interest now, viruses survive for longer periods at low humidity so it is even more important to maintain optimal relative humidity between 40% and 60%. If the RH in your home is too low and you have a humidifier, start running it. If someone in your home is self-quarantined, place the humidifier in the isolated person’s room. Provide individual level thermal control where possible.

Contributor: Lauren Hildebrand, Sustainability Director

The current pandemic brings us a renewed awareness of the materials in our homes and our environments. If you are like me, you are constantly tracking what you’re touching. Also, you may be thinking about how a virus to remains viable longer on some materials than others, as some preliminary research indicates. Luckily, thoughtful and responsible choices can help increase our health and wellness as our household spaces become full-time work, education and play spaces.

How can what we are learning affect our materials choices for current and future buildings? First and foremost, think about cleanability. How easy or difficult is it to disinfect a given material with, say, soap and water, or a diluted bleach solution? (Note that while our green cleaning protocols would not ordinarily include bleach and the current coronavirus can be destroyed with simple soap and water, there may be another virus in another time when we need to use something stronger.) How many grout lines or other transition materials are used, how cleanable are those transitions, and can we choose materials that minimize those transitions (such as continuous flooring or larger wall tiles)? We expect to see a renewed focus on cleanable materials that will ultimately improve health and durability under ordinary circumstances (and extraordinary circumstances).

We also foresee a surge in anti-microbial finishes. Be careful with those, because while they are designed to kill or inhibit the growth of microorganisms, many antimicrobials contain triclosan and triclocarban, which have shown to interfere with normal human development and function. For that reason, we advocate for targeted use.

Another concept to consider is no-touch building finishes and amenities. It seems to me that in a post-COVID-19 world, we will be choosing touchless automatic door openers and elevator buttons, more lighting occupancy sensors, touchless water-bottle refill stations, and those touchscreens in the lobby or checkout counter will be a thing of the past. Hopefully, we will have a touchless handwashing station in every new building lobby!

Contributor: Maureen Mahle, Managing Director, Sustainable Building Services

As the goals of Universal Design suggest, an integral part of designing high performance spaces for all people regardless of age or ability, includes incorporating health and wellness into the built environment. Many of the concerns targeted in health and wellness design strategies, such as chronic respiratory disease, diabetes, heart disease, and chronic illness, qualify as disabilities under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Further, each one of these health concerns is an underlying condition highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Addressing public health issues through design can contribute to promotion of overall health, avoidance of disease, and prevention of injury. (Steinfeld and Maisel, 2012).

There are several shared goals and design strategies among health and Universal Design initiatives — the improvement upon ergonomics, sleep, safety, physical and mental health, among others – not only serve to create healthier environments, but can also contribute to better spaces for all building occupants. Moreover, the inclusion of health strategies in design can assist individuals currently living with disabilities by mitigating chronic symptoms or preventing certain disabilities or injuries from occurring.

For more information about this topic, read the original piece in WBGC, and this article from WELL Building Institute.

Contributor: Peter Stratton, Senior Vice President, Managing Director, Accessibility Services

Created by the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI), the WELL Building Certification Program is focused on human health, mental wellness, community engagement, and overall comfort and well-being. It is the first building program to delve so deeply into these topics.

Organized into concept categories with mandatory preconditions and point-weighted optimizations, the most recent version, WELL v2, has ten concept categories: Air, Water, Light, Nourishment, Movement, Thermal Comfort, Sound, Materials, Mind, and Community. Utilizing industry standards set by the EPA, ASHRAE, CARB, SCAQMD, and CDPH, and others, the IWBI created these concept categories to incorporate all areas where occupants interact with a building and ways in which occupants’ health could be improved.

The IWBI requires on-site performance testing verification prior to the project achieving WELL certification. By incorporating performance verification for air, water, light, thermal comfort, and sound, the IWBI’s third-party testing agents prove that the project’s design and installed materials match the requirements as prescribed. What’s more, to ensure that the building remains certified under the WELL system, on-going performance verification is required every three years.

The ten concept categories outlined by the WELL Certification Program are incredibly important to ensuring both proactive and reactive health outcomes for humans.

Here is a Harvard study on long-term exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States of interest currently.

Contributor: Sarah Nugent, Sustainability Director

If you have listened in on one of the many webinars recently talking about human health and the built environment spurred by COVID-19, chances are you have heard from one of the healthy building advocates at the Center for Active Design. The Center oversees the Fitwel certification systems for healthy buildings and communities. Coincidently, I am currently working on Fitwel design reviews for three different multifamily projects, and I have a renewed appreciation for how the rating system addresses health issues relevant right now. Probably the most powerful and unique elements of the program are not the indoor air quality plans (although we are all obsessed with proper ventilation and humidity and filtration during quarantine), but the ways the program addresses the connection between physical inactivity and mental health. Without our normal incidental exercise, we are more acutely aware of needing opportunities to move our bodies within our homes and in our immediate neighborhoods. And secondarily, the other elements of Fitwel that affect mental health have been very much on my mind lately: daylight, views of nature, operable windows, a vegetable garden to plant, or acoustic comfort from exterior or interior background noise. Heaven knows we have enough acoustic distractions from screaming kids and barking dogs on our Zoom meetings without adding in the noise from the air handler or exhaust fan. If you are looking for more ideas about what can you can do to make your current or future project a bit healthier, visit the Fitwel Resources page: https://www.fitwel.org/resources.

Contributor: Maureen Mahle, Managing Director, Sustainable Housing Services

Mold, radon, carbon monoxide and toxic chemicals in homes contribute to poor indoor air quality and can lead to serious health problems. Clean air is beneficial to anyone, but it is especially important for those with respiratory conditions. Created by the US EPA, Indoor airPLUS Construction Specifications require that a newly built home includes additional protections to address moisture control, radon resistance, pest prevention, improved HVAC systems, reduced combustion pollutants, and low-emission materials. The goals and benefits of Indoor airPLUS qualified homes include improved indoor air quality, minimized pollutants, and protection against combustion pollutants. As an added layer, all Indoor airPLUS homes must first earn ENERGY STAR certification, improving energy efficiency and comfort as well. For more information on this certification, visit the EPA website: https://www.epa.gov/indoorairplus/basic-information-about-indoor-airplus

The building industry, like many others, will likely see significant changes and shifting priorities based on our current global crisis. As we learn the lessons set forth by current challenges, our team is committed to creating, adopting, and guiding best practices to improve the health and safety of the built environment.

Contributor: Jayd Alvarez, Marketing Coordinator

Jayd Alvarez