Blog

A high-level summary of the code development process with respect to the 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), aka the “model” energy code.

When I first started working at Steven Winter Associates, I didn’t know that one day I’d find myself involved in the development of codes and standards that impact how our buildings get built. I certainly don’t consider myself an expert, but I have learned a few things the hard way and thought they’d be worth sharing if you might be new to it.

So, here’s my very high-level summary of the code development process with respect to the 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), aka the “model” energy code. If you are looking for more detail, the ICC webpage has plenty of resources and a more detailed infographic than the one we’re showing and discussing here.

To start at the top of the image, the IECC is updated every three years. You’ve probably heard of the 2009, 2012, 2015, or 2018 IECC. ANYONE is permitted to propose a change, but it follows a very strict schedule. The deadline for 2021 IECC was January 14, 2019. Hundreds of proposals to change the 2018 IECC in time for inclusion in the 2021 IECC were submitted online to the International Code Council (ICC).

The merits of these proposals are then debated in two public settings: the Committee Action Hearing (CAH) and the Public Comment Hearing (PCH). At the Committee Action Hearing, proponents and opponents set out to convince the dozen or so voting members of the Residential or Commercial Energy Code Committee, which way to vote. After the CAH, all proposals are posted online with the Committee’s reason for voting for or against each one and their vote tally.

Once the Committee votes are posted, there is an online “public comment” period, where the proposal may receive comments from ANYONE, either in support of the code change or against it. The comment can even propose changes to the wording of the original proposal. If even one public comment is submitted, the proposal needs to be debated again at the Public Comment Hearing (PCH), where instead of a pre-selected committee of voters, it’s a room full of ICC voters (generally 50-100 code officials) that get to vote on it. Therefore, the goal of a code change proposal is to get approved at the Committee Action Hearing and hope that no one submits a public comment! In that case where no public comment is submitted, that code change proposal makes its way into the next IECC. That’s the easiest path, but there are others.

If a code change proposal doesn’t get approved at the CAH, and public comments are submitted, the proposal can still be successfully defended and make its way into the model code. It’s just one more hurdle to clear, and in some cases, the number of voters to convince can be higher. More on that nuance later. On the flip side, code change proposals approved by the Committee can face public opposition during the comment period and at PCH and also ultimately not make it into the code. We’ll go through some examples in a bit.

Those two public processes lead us to the final stage where the “Online Governmental Consensus Vote (OGCV)” happens (and is happening now for the 2021 IECC). “Governmental Member Voting Representatives”, comprised of local and state government officials, like the Fire Department or local Department of Buildings, have access to all the original proposals as written, how the Committee voted, what their reasons were, what public comments were submitted and why, and whether the Committee’s vote was upheld or overturned by the ICC voters at the Public Comment Hearing. Voters also have access to a searchable video library of the testimonies delivered on each proposal at both the Committee Action Hearing and the Public Comment Hearing.

I won’t get into all the gory details here but depending on how the votes played out at the hearings, getting a code change proposal approved for 2021 IECC could either require a simple majority (50%+1) or a 2/3 majority. Getting a code change proposal disapproved only ever requires a simple majority.

So, let’s take that background and use some examples to demonstrate how 3 different proposals can either fail or make it into the code.

Example 1: A commercial energy code change proposal is submitted. The Committee doesn’t like it and they vote to “Disapprove” it. The original proponent then submits a public comment and tries to defend the merits of the original proposal at the Public Comment Hearing. Because the Committee didn’t support it at their Hearing, this proposal now requires 2/3 of the voting members present at the PCH to support it, by casting an electronic vote once all testimony has been heard. In this example, the proponent is unsuccessful and the PCH voters also vote to “Disapprove”. In the final online vote, the online voters, perhaps seeing that both previous voting bodies voted to “Disapprove” also decide that is the way to go, so that code change doesn’t make it into the 2021 IECC.

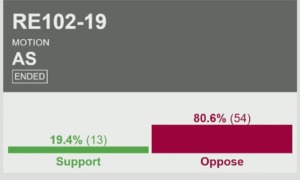

Example 2: A residential energy code change proposal is submitted. The Committee does like this one and they vote to approve it “As Submitted”. Someone who disagrees with this vote submits a public comment, forcing it to be re-heard at the Public Comment Hearing. Even though the Committee supported it at their Hearing, an outcome of “Disapproval” just requires a simple majority at the PCH. In this example, those who disagree with the proposed code change are successful at arguing against the code change and the PCH voters vote to “Disapprove” and “overturn the Committee”. In the final online vote, the online voters look at the testimony for themselves and ultimately side with their fellow code officials who voted at PCH; they vote to “Disapprove”. So this code change also doesn’t make it into the 2021 IECC.

Example 3: A commercial energy code change proposal is submitted. The Committee doesn’t like it and they vote to “Disapprove” it. The proponent submits a public comment to CHANGE the proposal wording to address the Committee’s concerns, and tries to defend the merits of the proposal “As Modified by the Public Comment (AMPC)” at the Public Comment Hearing. Because the Committee didn’t support it at their Hearing, this proposal now requires 2/3 of the voting members present at PCH to support the modified version. In this example, they are successful at convincing 2/3 of the PCH voters to vote in support of the modified version and “overturn the Committee”. In the final online vote, the online voters, seeing the differing votes, look at the testimony for themselves and ultimately side with their fellow code officials who voted at PCH, and vote to approve. So this final code change example successfully makes it into the 2021 IECC.

If you’ve ever wondered why the energy code says what it says, it’s come to be in the code through this process. If you’ve ever wondered why the code hasn’t changed all that much over the last 10 years, it’s very hard to get a change approved since the bar for Disapproval is just a simple majority. But, if you are interested in getting involved in this process, don’t get discouraged (keep an eye out for another blog post on how an unlikely collaboration led to a small but effective change)!

May the codes be with you.

Contributor: Gayathri Vijayakumar, Director of Residential Energy Services

Steven Winter Associates